By MONTE DUTTON

It’s been a week. When I learned Dick Sheridan had died, I dropped everything and tried to write something that others would not. For most of a decade, I worked with and for Sheridan.

His greatness stands on its own merits. It doesn’t have to be exaggerated. As was the case on the day Dale Earnhardt died, it’s important to depict the man, not the myths. History professors told me that. Sheridan proved it.

I’m not unduly sad. Sheridan lived a long, productive, rich life. He was a man of indomitable will who demanded everything his players could possibly achieve, and it’s what happened, simple as that. The price of victory is sacrifice and dedication. Sheridan successfully taught his players and others around him that it was worth it. Fun? Nothing is more fun than victory.

He wasn’t perfect. Neither is anyone else. No one was ever better at putting a team on the field that exuded excellence and class.

Sheridan has never been far away since his death. As Kenny Rogers once sang [Alex Harvey’s words], he “still walks the furrowed fields of my mind.” If anyone ever wrote a song, a book or a movie about Sheridan, it would be an epic. He was larger than life. The memories linger and sustain us.

Now his life is to be recollected in a North Augusta park, where once he played ball and began learning how to coach it. He learned the values of simplicity and execution. He taught those under him how to win, and most of the difference between competing and winning is between the ears, with assists from the heart and the guts.

The personal effect is to get me thinking about football on the cusp of when it is to be played in earnest again. It stimulates longing for it amid the midsummer heat. I’m old, but I still watch vicariously.

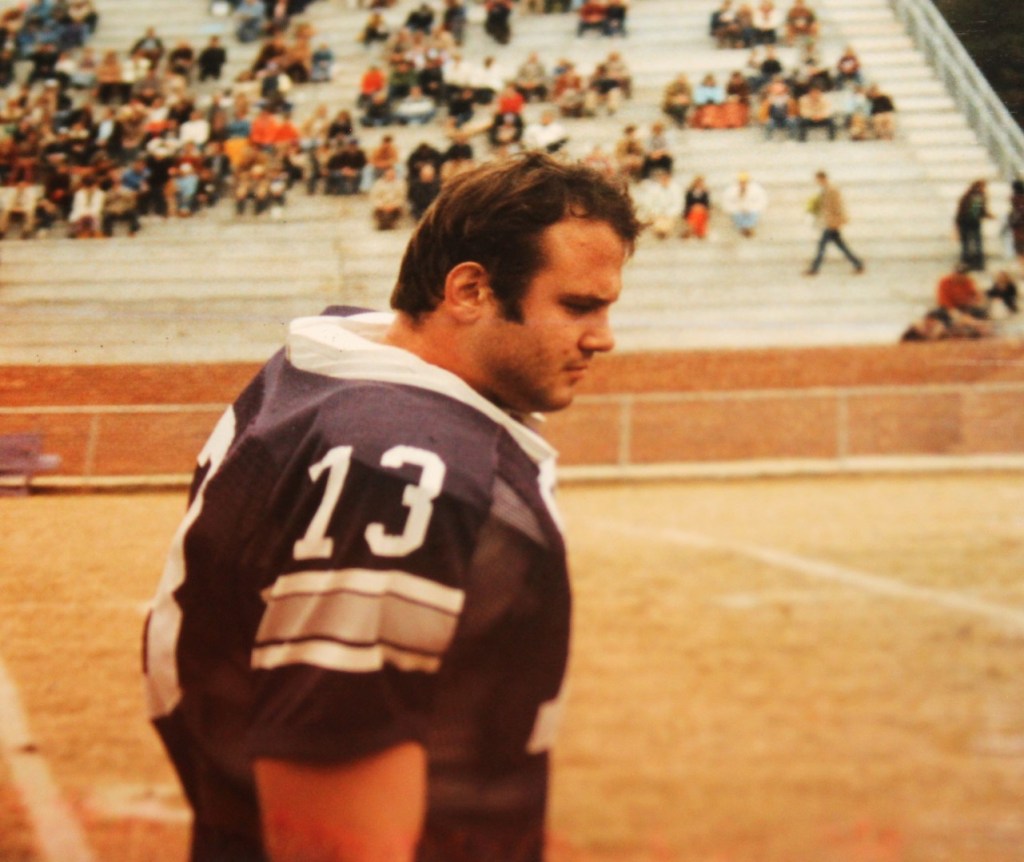

Sheridan was a hands-on coach with assistants who fit him like a glove. I remember the times that he would charge over to the defense on the practice field, rant and rave, then move to some other sector. Steve Robertson would watch him vent; then, when he left, he’d just tell the players to keep doing what they were doing. Jimmy Satterfield would mumble a little and shake his head. They all – Bobby Johnson, Robbie Caldwell, Ken Pettus, Eric Hyman, Ted Cain, Whitie Kendall and many others — knew him as well as they knew themselves. It all worked cohesively, with each assistant and every player handling adroitly his outpost of the empire.

Kendall was an ancient font of wisdom. The Hurricanes hero, Bob King, jogged around the fields at dusk, late in practice, wearing a gray sweatsuit that Bud Wilkinson might have worn. I called King “the Galloping Ghost” (like Red Grange). In hindsight, I should have discarded the alliteration and dubbed him “the Ancient Knight.” King played as a Hurricane and coached as a Paladin. I used ancient twice in one paragraph.

Trainers and equipment managers, of which I was the latter, had a unique view of all this subtle artistry.

As a writer, Sheridan and others taught me a career-long fascination with the difference between competing and winning. The fields and stadiums are full of coaches who raise the level but can’t quite get over that hump.

Great teams expect to win. They are bold and resourceful, and I’ve concluded that the difference is grounded in intangibles that can’t be measured in algorithms and metrics. The difference is defined in some spiraling ball soaring through the air, where one receiver makes a play and another thinks “please don’t drop it, please don’t drop it.”

Guess which one drops it.

Sheridan had a knack for producing playmakers who came through when it counted most. His teams stretched the realm of the possible to the point where it included most anything.

Another lesson of my time watching Sheridan coach is that teams laugh with, not at, great coaches. Everyone found some amusement – the way he tucked his windbreaker into his coaching shorts, and how he often looked as if he were posing for a portrait or a statue – but no one laughed at Sheridan even when they thought he was funny.

Football, like life, is serious business. In most cases, one leads to the other.

Sometimes it’s hard for athletes to adjust to a world beyond the chalk boundaries. It seems as if the world is run by people who get their frontiers fenced in. They never give up, though. Life is also a game of ordeal and triumph.

The spirit of a great man never dies. It lives in Clay Hendrix.

If you like my style, please support the coverage by making a contribution to DHK Sports, P.O. Box 768, Clinton, S.C. 29325, or, by becoming a patron, or, indirectly, by buying one of my books at Monte Dutton.net. Many thanks to those who support me.