By MONTE DUTTON

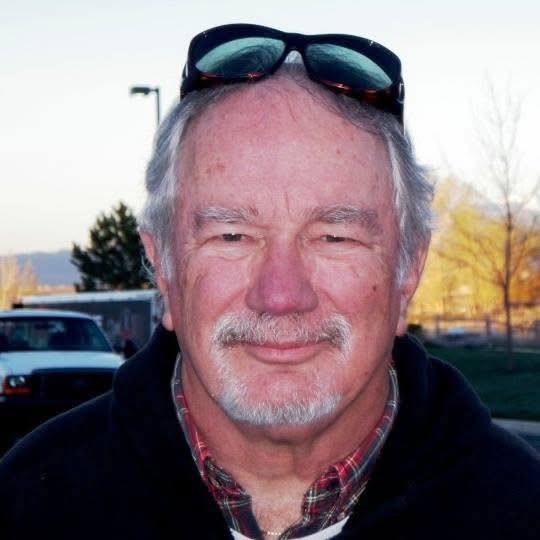

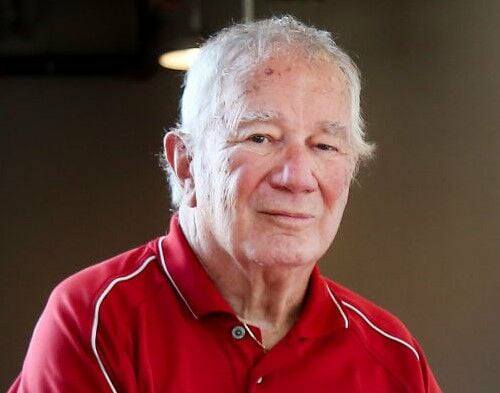

When I first started writing regularly about NASCAR as a way to make a living, I quickly gained acceptance in the media centers and press boxes because of two friends, Mike Hembree and Al Pearce.

Back in 1993, the NASCAR media corps was hard to penetrate. Veterans – Gerald Martin, Tom Higgins, Bob Myers, Benny Phillips, Greg Fielden. Steve Waid, Bob Moore, Larry Woody, Bob Latford, Ed Hinton, Jim McLaurin and many others – ruled the roost. Once writers got into NASCAR, they generally stayed. I angled for it a long time before I found a slot.

The general attitude among the long-timers was, “Who’s this guy think he is?”

I wanted to show all the vets I was knowledgeable, which I was. I’d followed NASCAR since I went to the 1965 Volunteer 500 at age seven. The first race I ever saw was won by Jarrett. Ned Jarrett. I saw Richard Petty win twice on dirt.

Hembree and I were already friends. When I worked in the Furman sports information office, Mike’s beat was the Paladins and NASCAR. When he got back from Daytona and covered the next Furman basketball game, he and I would talk about what happened at the 500.

Al and I got to know each other because my hometown was Clinton and his alma mater was Presbyterian College, even though he wrote about racing for the newspaper in Newport News, Va., and had more free-lance gigs than most “consultants.” Also, he and Francie were close friends with a relative of mine, Sandy Parks, a Clinton native and PC grad who is the daughter of my Uncle Winfred.

When Hembree and Pearce acted like I was all right, it made me all right.

For the next 30 years, Al often stopped by Clinton on the way to Atlanta or Talladega. He visited his favorite professor, Bill Cannon. After Cannon died, Al stopped by to have lunch with me, particularly after my newspaper job was eliminated in 2013. As a freshman, Al almost flunked out, and his father drove down from Rocky Mount, N.C., to take him home. Cannon convinced Al’s old man, who worked for the railroad, to give him another shot, or else Al would have worked on the railroad, too., presumably “all the live-long day, just to pass the time away.”

Al gave Bill Cannon credit for the course of his career.

Petty won the first race Al ever covered, in Dover, Del. Al told me more than once the first question he ever asked. He asked The King why he climbed out of the window of his Plymouth instead of just opening the door.

“You ain’t been to many of these races, have you, son?” Petty asked.

That was in the 1960s. Al wrote about racing nearly three times as long as I did.

I mentioned that Al did a lot of free-lance writing, which is why he made it to many races where his newspaper didn’t pay the tab. At a lot of far-flung tracks, he had friends who put him up on race weekends. When one of those liaisons fell through, once he slept on the floor of the room in Fort Worth that Kenny Bruce and I were sharing. Al could stretch a dollar. He had to.

Al was an inspiration of one of my favorite sayings. A writer retires when they find him head down on a keyboard, with X’s streaming across the screen. He was a lifer who honed his craft and fought the good fight.

Albert Pearce died on Wednesday at 82 and wrote about racing for 56 of them. It was after he served his country in Vietnam. He and I exchanged emails just a few days ago. When I was in the hospital in January, he and Hembree came to visit.

Because he was older, Al was more crotchety than me. Bill Cannon was more crotchety than Al. I’ve still got some time, though.

A delegation of sportswriters, Al among them, had a grand time having lunch before attending the funeral of another great colleague, Jim McLaurin, a little over a year ago. For those who live long, productive lives, it ought not be sorrowful. Mainly we shared outrageous stories about our departed pal.

The memories, they sustain us.

A word of advice: never read an Internet sports story with a headline that begins, “Calls mount …” You are wasting your time.

Buy my books. A lot of them are on Amazon. Most of them are fiction. This website satisfies my need for real life.

The Latter Days is the story of Clyde Kinlaw, a baseball scout who finds a bright prospect in the middle of nowhere and tries to develop him and prove his detractors wrong.

Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell is a story of a group of restless souls who unwittingly get themselves involved in a national conspiracy involving big business, politics and foreign interference.

Lightning in a Bottle and the sequel, Life Gets Complicated, are about rebellious young stock-car racer Barrie Jarman.

Lightning in a Bottle and Cowboys Come Home, about two Texans home from World War II, are also available in audio versions.